Poor Children of London's East End by Matthew Broadhead and Emily Gallagher

Emily Gallagher is an independent researcher specialising in Victorian dress and cultural history, museology, and material culture. She has kindly provided the following interpretation of this fascinating carte de visite to kick off an in-depth analysis.

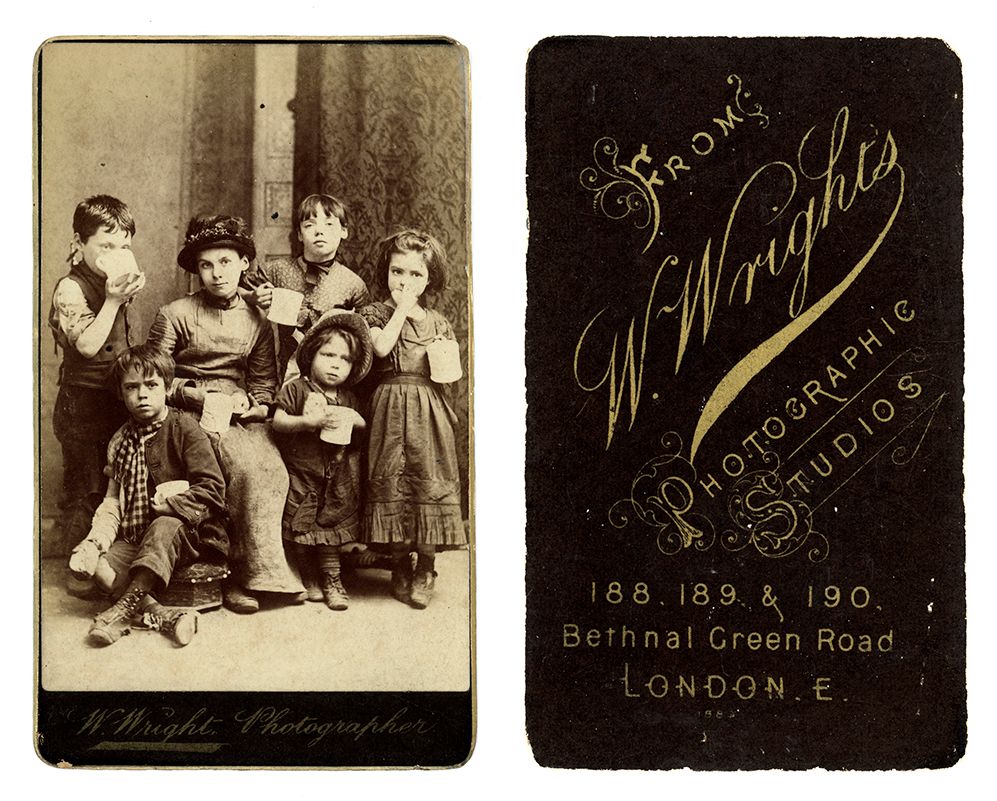

Spitalfields Nippers and Their Dress as Photographic Subjects

An acute awareness of the power of photography as a commercial, artistic, philanthropic and documentary medium was well established in the intentions and initiatives of Victorian photographers by the decade in which this photograph was created. Since the 1860s - mirroring the work of social reporters, such as Charles Booth who will be discussed - photographers had actively turned their lenses to the urban working-class and poor in order to record and spread awareness of the existence of underrepresented social strata.

The first and most notable endeavour of such was that of Henry Mayhew, whose 1861 edition of London Labour and the London Poor, provided readers with vignettes of the city’s lower orders. Mayhew’s unrefined street photography captured London’s workers and poor impromptu, with the intention of sharing insights into the lives of a group that his middle-class contemporaries knew little about. Following Mayhew’s work, efforts were continually made to capture the Victorian and Edwardian working classes and poor. In 1912, photographer and philanthropist Horace Warner published photographs of ‘Spitalfields[‘] Nippers’; a series of naturalistic images that captured the children of London’s east-end slums (who are not dissimilar to those in the photograph here). Meanwhile, photographers across England captured the lower classes at work. Francis Meadow Sutcliffe recorded Whitby’s fisherwomen, while Wigan-based Robert Little and John Cooper favoured local women miners, known as ‘pit-brow lasses’. And, as the photograph in question evidences, William Wright was yet another photographer who captured and recorded the Victorian lower classes.

Created during the 1880s, Wright’s photograph has denied the ephemeral nature of carte de visites (visiting cards traded between friends and acquaintances), whereby the photograph still exists as a record of a social strata who are underrepresented in museum collections and archival records. However, unlike the photographs of Mayhew, Warner and Sutcliffe, its subjects have been removed from their everyday surroundings. Therefore, within the distinctive setting of the Victorian photographer’s studio, it is their clothes that offer us insight into the social and sartorial experiences of the children.

Little is known about the clothing of the Victorian poor. Unlike the workers of England’s industrial northern cities, who earned a comfortable wage and could therefore often purchase respectable clothing, the dress of London’s slum dwellers were bought second-hand and worn until threadbare. Thus, the tattered nature of the children’s clothes is not uncommon. Victorian children often wore second-hand clothes and cast-offs from elder siblings and in turn regularly fell victim to patched, darned and ill-fitting clothing. For their parents, this was a way to stretch the little money they had and prolong the existence of costly commodities. Petticoat Lane - a stone's throw away from Bethnal Green Road where the photo was taken - hosted a second-hand clothes market that likely clothed the children seen in the photograph. Shoes and boots were sold in abundance, polished and ‘translated’ to be sold to those in desperate need of footwear. While their northern counterparts wore wooden-soled clogs, London’s child population could be found in boots. The boy on the bottom left sits with his legs crossed, his boots bursting at the seams, while those worn by the girl on the far right are laceless. Their shoes were likely the only pair they owned and were perhaps only worn when absolutely necessary as more often than not, poor Victorian children ran around barefoot.

For the Victorian middle and upper classes, having one’s photograph taken offered the opportunity to wear one’s finery. A lady’s favourite ensemble would be worn in front of the camera in order to capture her at her best. However, for the working-class and poor, sartorial possessions were few and any spares were recurrently pawned. Albeit, the two girls in the centre of the photograph can each be seen wearing a hat and bonnet, which, as dress historian Madeleine Ginsburg’s study of the Victorian second-hand clothes market revealed, were often bought new at a price just as cheap as second-hand items.

The girl standing above the infant wearing the bonnet wears what seems to be a cotton printed dress, which during the decade in which this photograph was taken, are said to have been chiefly worn by working-class women and girls. However, determining its colour and the exact fabric is encumbered by the sepia tone of Victorian photography. Nevertheless, while it may be presumed that the clothes they wore were drab and washed-out, fabric samples in the collection of The Foundling Museum, London - a former site where destitute mothers left children they could not care for along with fabric tokens in order to later identify their child - evidence that the poor did in fact wear a variety of vivid colours and prints. It is evidence such as this that historians now rely on to reveal the material reality of the dress of the poor. Additionally, photographs offer insights into the clothes and sartorial experiences of this underrepresented social strata of the past. Thanks to a number of pioneering Victorian reporters and photographers, photographs of the Victorian working-class and poor survive in abundance; many of which were bought and sold as curiosities that satisfied the middle-class fascination with otherness, while others were the result of genuine philanthropy.

Though evidence shows that William Wright was involved in local charity, we are unable to confirm the intention and motive behind the photograph in question. As noted, unlike those in the photographs of Mayhew, Warner and Sutcliffe, Wright has placed his subjects in front of the photographer’s curtain. Photographs of this nature were common - Arthur Munby, a Victorian philanthropist who collected photographs of working-class women, grumbled that photographs of the working classes ‘au naturel’ were hard to come by - and often criticised as tear-jerking publicity stunts similar to contemporary slum tourism (a leisure activity that saw middle-class onlookers pay to gawp at the ways in which the other half lived). The photos were said to “portray[...] poor children as victims of their economic circumstances [...], degrading them further by the act of photography itself” (The Gentle Author in Warner 2014, p.9), by placing them in an unfamiliar setting and providing them with nothing in return. In 1868, philanthropist Dr Bernado was taken to court for such.

Wright’s motives are unknown and with little documentation accompanying the photograph, one can only speculate. There is no evidence that the photograph was intentionally conceived as tear-jerking ephemera or to satisfy the curiosity of tourists, however, we also cannot confirm that it was the result of a virtuous philanthropic venture. Nevertheless, the photo has captured the likeness of six children whose existence may have otherwise been lost and forgotten. And although they testify the common stereotype that the Victorian working-class and poor had minor sartorial experiences or simply wore rags, their individual dressed appearances (which differ - albeit slightly - from their contemporaries in the photographs of Warner and Mayhew) and ways in which they may have acquired the clothes they wore, deny the homogenisation of this underrepresented and misunderstood social strata of the past.

Bibliography

Warner, H. (2014) Spitalfields Nippers. London: Spitalfields Life Books.

The Object Itself

We can see from looking at this carte de visite that it came from W. Wright’s photographic studio situated at 188, 189 and 190 Bethnal Green Road in London's East End.

Immediately it is possible to note that this object dates to the 1880’s, as an exact year is visibly printed near the bottom reverse side. Even with a loupe the last digit is unclear, but other examples with the same advertisement design feature the years 1883, 1884 and 1885. This is consistent with information published on the Museum of London’s photoLondon website (researched and compiled by David Webb) which states that the photographer occupied this address between 1884 and 1892. Looking at dated mounts has determined that he was occupying all three addresses from 1883 not 1884. Over his photographic career, W. Wright (credit to PhotoLondon) had at least fifteen separate studio addresses. These were as follows:

1. 12 Millfield Place, Green Lanes, Stoke Newington from 1877 until June 16th, 1881. Absorbed into Green Lanes on June 17th, 1881.

2. 189 and 190 Bethnal Green Road, Bethnal Green between 1879 and 1884.

3. 69 Green Lanes, Stoke Newington from June 17th, 1881 until 1884. This was a printing works.

4. 188, 189 and 190 Bethnal Green Road, Bethnal Green from 1884 until 1892.

5. 98 Cheapside, City of London (3 floors) from 1884 until 1896. Successors to William Henry Prestwich; succeeded by Club Photographic Co.

6. 71 Green Lanes, Stoke Newington from 1886 until 1891. This was a printing works succeeded by Robert Hellis.

7. 10 Upper Street, Islington from 1886 until 1891. Successors to George and John Springthorpe; succeeded by Edward Sharp.

8. 81 Whitechapel High Street, Stepney from 1886 until 1895. Successors to William Hobbs.

9. 422 Mile End Road, Stepney 1889 - 1898. Successors to Thomas John Barnes; succeeded by Henry Francis Turner.

10. 83 Bishopsgate Street Without, City of London (3 floors) from 1891 until 1909. Renumbered as studio 14 in 1910. Bought by Alfred James Lewis 1900. Aka Adam and Eve Buildings.

11. 189 Bethnal Green Road, Bethnal Green from 1893 until 1896.

12. 232 Mare Street, Hackney from 1893 until 1897. Successors to Richard Beckett; succeeded by Hellis & Sons.

13. 93 Whitechapel High Street, Stepney from 1896 until 1899. Succeeded by Frederick William Lewis.

14. 266 Bishopsgate, City of London (3 floors) March 1st, 1910 until 1911.

15. 21 Broadway, Stratford

It must be assumed that there was activity on either side of these parameters, but it is possible to deduce from this list that Wright studios were operating for at least 34 years between 1877-1911. We also know that this particular carte de visite was created within the first ten years of his photography studios being open for business.

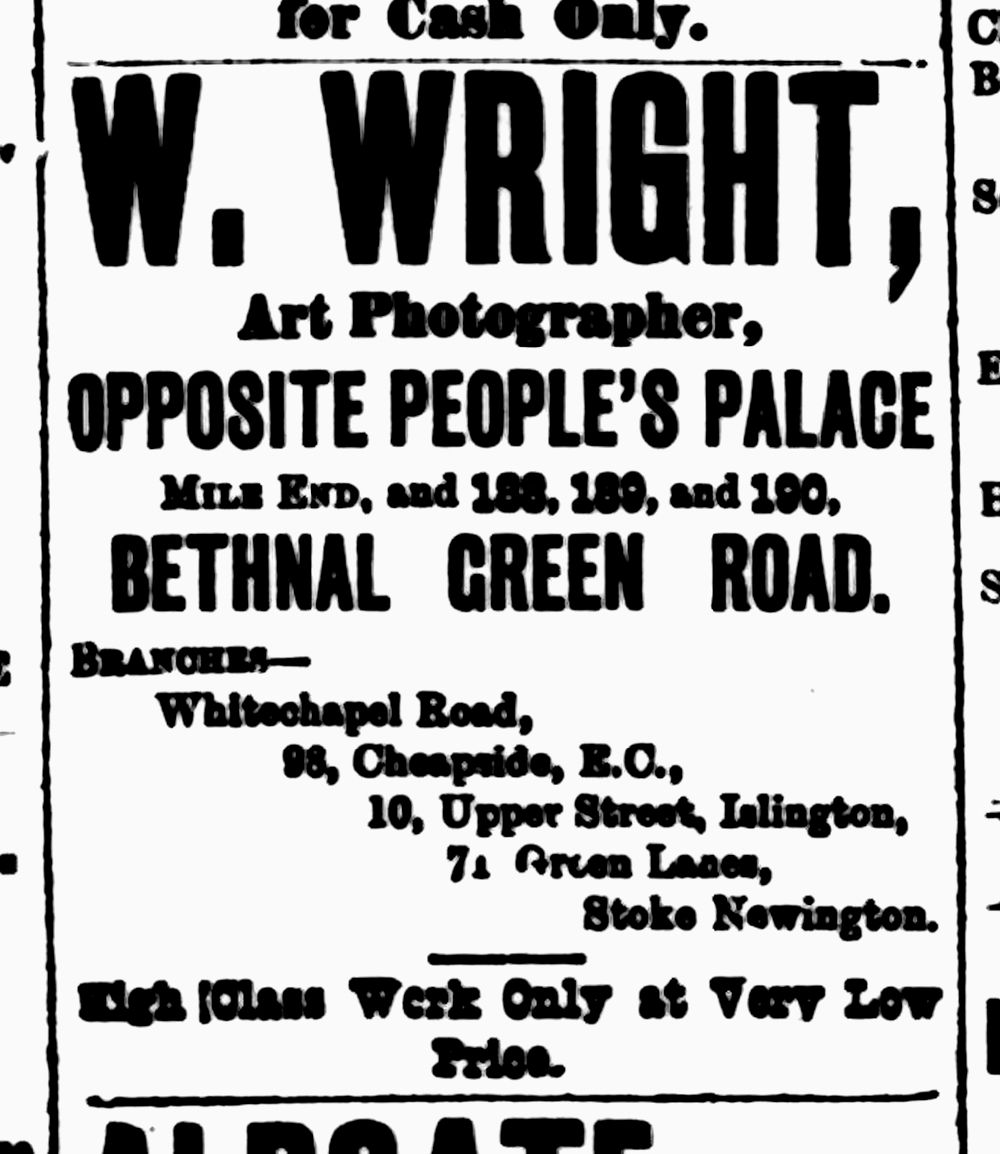

The advertisement below dates from 1893, around ten years after the carte de visite was made. It stands out that W. Wright's two main studios were situated on Mile End Road and Bethnal Green Road. Wright opening a studio branch opposite The People's Palace (opened in 1887 by Queen Victoria) would have made perfect sense considering it was major venue for culture, entertainment and education in London's East End. The original Palace was where the Queens’ Building is located today and included a large concert hall called ‘the Queen's Hall’, a library (now known as The Octagon), Winter Garden, swimming pool, gymnasium, gardens and tennis courts. It was designed to enrich the lives of local people with shows featuring donkeys, art, dances, and large scale concerts which also served as a distraction from 'gin-palaces'.

According to the census taken in 1881, a William Wright is described as a photographer aged 25 who is living with his wife Sarah. They have two sons named William George and Albert Edward at 190 Bethnal Green Road in Middlesex, East London. Living at the same address, Elizabeth Harris (age 17) is employed as an assistant and servant. The transcriber decided that William Wright was female although this was obviously not the case, so it was necessary to check the actual document in question. It was found that they were correctly identified as male but his age of 21 suggests they may not be the William Wright whose business is advertised on the mount. The following newspaper story published in the East London Observer on Saturday 5th January 1889 provides further evidence that the William Wright recorded in the 1881 census is possibly a son or other relative of the William Wright, the ‘original photographer’:

Wright, William (North-East Bethnal Green), is an example of what can be done by industry, combined with shrewd business qualities. It is now many years ago since he first started in business as an art photographer in the Bethnal Green-road, where, by the excellent quality of work, he speedily gained a reputation. As his business increased he found it necessary to considerably extend and increase his premises, the result being that at the present time there is scarcely any quarter of the metropolis that does not contain one or more of Mr. Wright's photographic establishments. Mr. Wright's is, and has been, one of the most familiar forms at every public gathering or fete connected in any way with Bethnal Green for considerably over a half-century of years indeed, no gathering of any importance in the locality is considered successful unless its negative has been preserved for all time by means of one of Mr. Wright's cameras.

Six years ago, he was elected to the Bethnal Green Vestry, at which he has been one of the most dutiful of members, attending as he has done, the 1 majority, not only of Vestry meetings, but also of the meetings of the Committee to which he has been elected. His connection with the Bethnal Green Board of Guardians dates from three years ago, when he was returned at the first asking by a very large majority. He has taken an active interest in all the local charities, and has done much to promote their success. Having recently retired from active business life, he has a considerable amount of time on his hands, which he is prepared to devote, if elected, to the promotion of the claims of the district on the new County Council.

He has taken an active interest in all the local charities, and has done much to promote their success” could be the key to understanding why this photograph with unusual subject matter was taken.

It is not possible that “for considerably over a half-century of years indeed” could be correct, as even fifty years before 1889 was the year that Louis Daguerre and William Henry Fox Talbot simultaneously invented photography. We also know that Wright’s earliest photographic studio based at 12 Millfield Land, Green Lanes, Stoke Newington was operated from 1877 which is only twelve years prior to this piece printed in the East London Observer. Another aspect to consider is that this piece was written in connection with the photographer’s independent candidature for London County Council, so it is entirely possible that some exaggeration has taken place.

That last piece (which suggested that Mr. Wright put themselves forward as a candidate for the newly formed London County Council) is explained in more detail by the following advertisement found in a local newspaper:

ELECTION FOR COUNTY COUNCIL.

VOTE FOR W. WRIGHT,

Independent Candidate for the North-East Division of Bethnal Green.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Having, for some considerable time, been pressed to come forward as a candidate for the County Council, I now consent, and if, by consenting, I can be of any service to my Friends and Neighbours in helping to carry out the bold scheme of County Government, it will lead, I hope, to a higher conception of our duties to one another in this great London of ours; and will more than amply repay me.

My views on some of the more prominent subjects that are before the Public are as follows, and I earnestly hope you sympathise with them, if not, I should have refrained from being a Candidate. The public sentiments existing in this district, are well-known to me, having been connected with its many Associations, philanthropic, and otherwise for many years past.

1. Reform of existing abuses in connection with the Asylum and other Local Boards.

2. Should, if elected, strenuously oppose the renewal of the Coal Dues, as it operates harshly in limiting and making Dearer the warmth necessary in the humble homes of the poor.

3. I am in favour of Equalization of the Poor-Rate, so that every person should pay their just share, and No More, to the Common Fund for the Relief of the Poor.

4. Should also advocate that the Unemployed of the District be employed (as far as possible) on Works that would be needful to the district without Pauperising the Workers; and in reference to Public Works, all should be publicly Tendered for, on one condition only, namely; that the work be properly carried out.

On other questions that any misgiving should arise in my mind in dealing with it, I should feel it a duty to confer with you on the subject. I should earnestly support any well devised scheme for easier communication with the other side of the Thames.

Yours faithfully,

WILLIAM WRIGHT,

Photographer,

188 and 190, Bethnal Green-road.

MR. GEORGE HAY, MR. JOHN HEATH – Hon. Secs.

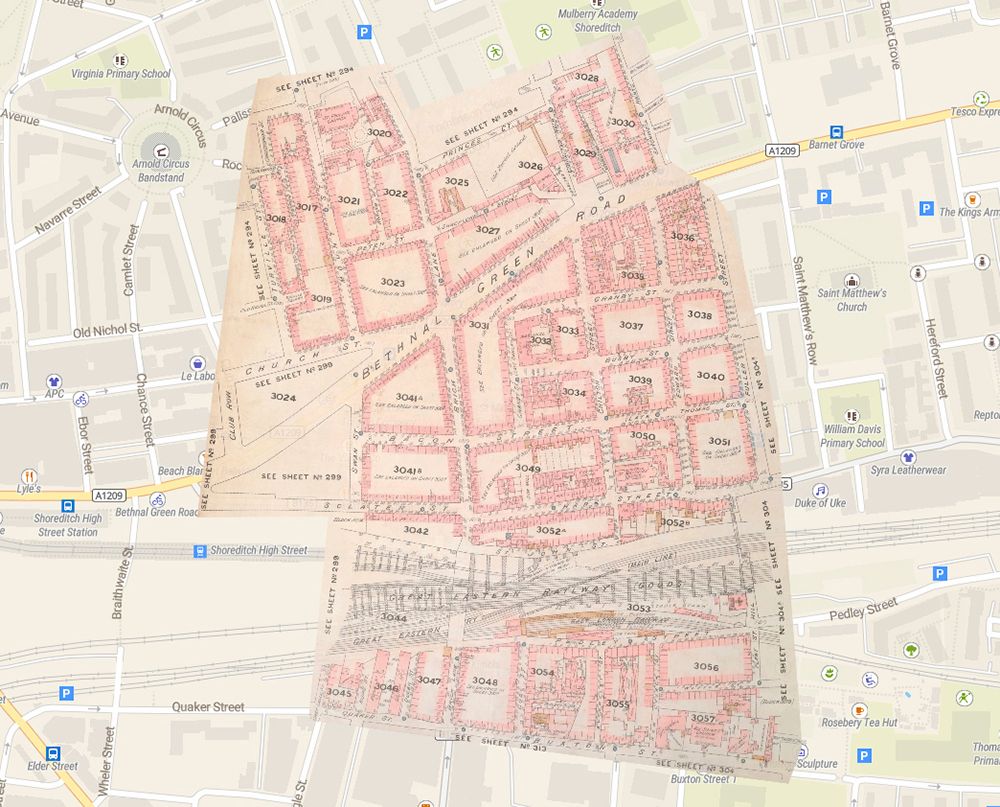

None of the buildings that this business occupied still exist in the present. Although many of the Victorian buildings along this busy East End thoroughfare have survived in various states, there is a 50-yard stretch within which the photographic studio would have been located. This now consists of post-war housing estates on both sides, which may have been built to replace buildings that were destroyed by bombing raids during the Second World War. It is also possible that they were demolished as part of post-war slum clearance that took place across the United Kingdom. Despite the loss of the original buildings, it is still possible to obtain a good idea of what the studio may have looked like, as just a few yards in either direction are buildings that date back to the nineteenth century or earlier.

By using the Goad Insurance Plan of London shown below, it is possible to deduce that 185 Bethnal Green Road (above) was situated directly opposite where W. Wright's studio at 188, 189, and 190 would have been.

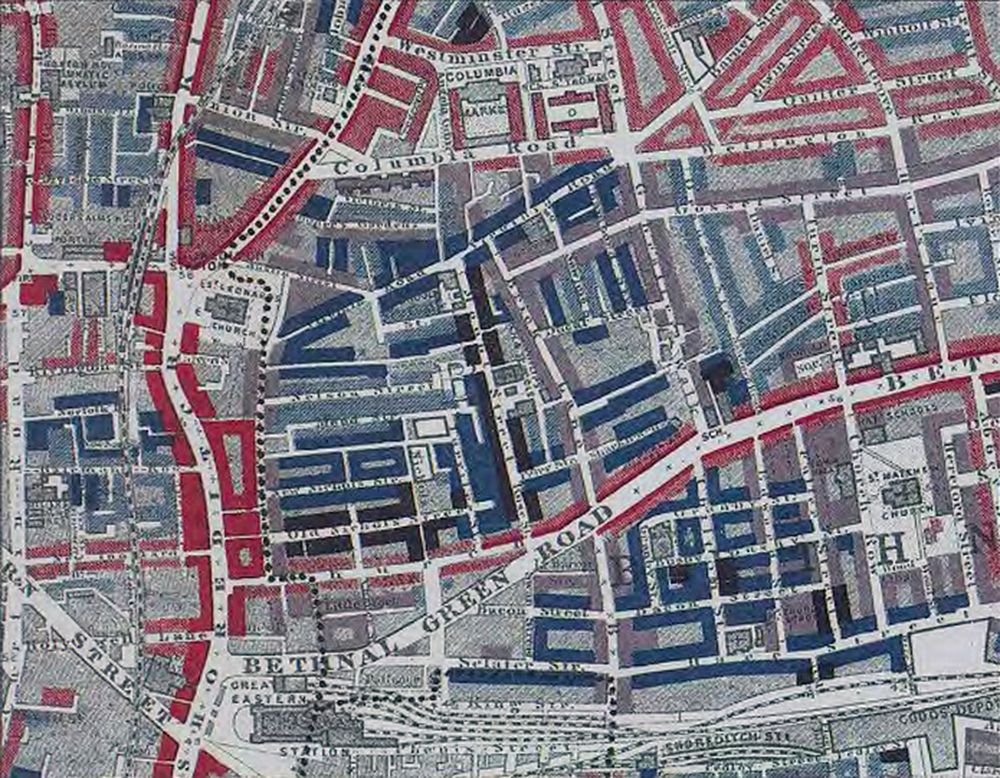

Booth’s ‘Descriptive Map of London Poverty’ published in 1889 was based on information gathered from School Board visitors. A first sheet covering the East End was published in the first volume of Labour and Life of the People, Volume 1: East London (London: Macmillan, 1889) as the Descriptive Map of East End Poverty. The map was expanded in 1891 to four sheets - covering an area from Kensington in the west to Poplar in the east, and from Kentish Town in the north to Stockwell in the south - and published in subsequent volumes of the survey. These maps are collectively known as the Descriptive Map of London Poverty 1889. They used Stanford's Library Map of London and Suburbs at a scale of 6 inches to 1 mile (1:10560) as their base.

Coloured street by street to indicate the levels of poverty and wealth, this enquiry was widely circulated and commented upon at the time. Ten years later, as the inquiry was still progressing, it was thought necessary to revisit the maps and a second series was produced, the Maps Descriptive of London Poverty 1898-99. These were based on the observations made by investigators accompanying policemen on their beats around London. The following key is applicable to both series:

Gold: Upper-middle and Upper classes. Wealthy.

Red: Well-to-do. Middle-class.

Pink: Fairly comfortable. Good ordinary earning.

Purple: Mixed. Some comfortable, others poor.

Pale Blue: Poor. 18s. to 21s. a week for moderate family.

Dark blue: Very poor, casual. Chronic want.

Black: Lowest class. Vicious, semi-criminal.

Bethnal Green Road was mostly classified as red or pink, which denotes middle class, well to do and comfortable. The 1889 map shows every street behind the photographic business to the south as almost entirely dark blue. This area bounded by Bethnal Green Road to the west and Hereford Street to the East, was mainly populated by those who were very poor with casual chronic want. There are even parts of this marked black which suggests that the lowest class of vicious, semi-criminals were also present. A slum area to the northwest known as ‘Old Nichol’ was similar and particularly notorious. When comparing both maps side by side, it is possible to see that the Old Nichol was completely redeveloped. Previously recorded as the two lowest categories (dark blue, black) these were replaced by gold, which constituted the wealthy upper and upper-middle classes. This is evidence that a social cleansing exercise was completed over a ten-year period.

The decision was made to look more closely at the history of this particular area, it was found that the current Boundary Estate, constructed from 1890, was one of the earliest social housing schemes built by a local government authority formally opened in 1900. It was built on the site of the demolished Friars Mount rookery in the Old Nichol, with works begun by the Metropolitan Board of Works in 1893 and completed by the then recently formed London County Council. Soil from the foundations was used to construct a mound in the middle of Arnold Circus at the centre of the development, surmounted by an extant bandstand. Consisting of multi-storey brick tenements radiating from a central circus, each bears the name of a town or village along the non-tidal reaches of the Thames.

The Morning Post published on Monday 5th March, 1900 reported a speech given by the Prince of Wales which was prefaced with a description of the slum clearance that took place and the perceived benefit of the new development.

"On Saturday, the Prince and Princess of Wales visited Bethnal-green for the purpose of taking part in the formal opening of the large blocks of workmen's dwellings erected by the London County Council on what is known as the Boundary-street area, Bethnal-green. The estate is fifteen acres in extent, and was formerly covered with some of the worst slums in London, its death rate in 1889 being over 40 per 1000, or nearly twice as great as that of the parish of Bethnal green. Under a scheme adopted by the London County Council in 1890 the slums have been swept out of existence, and blocks of wholesome dwellings have been erected in their place capable of accommodating 5,380 persons. The buildings are so arranged that the living room of every tenement receives the benefit of sunlight at some time during the day, and a circular breathing place planted with shrubs and provided with seats has been left in the centre of the area."

In his speech the Prince of Wales gave a literary insight into the history of the former slum area saying: "I find that even as long ago as 1839 Dr. Southwood Smith gave a melancholy account of his inspection of the slums in this neighbourhood and elsewhere in the Metropolis. Lord Nelson’s captains had a sorry fate when their names were borrowed to distinguish the streets and lanes of the foul area which these fair buildings have replaced. Few indeed will forget this site who have read Mr. Morrisons pathetic tale of "A Child of the Jago.” and all of us are familiar with the labours of that excellent philanthropist, Mr. Jay, in this neighborhood. More than forty years after Dr. Gavin wrote his book the death rate of the persons living in this area was 40 per 1000, and some more radical improvement was necessary. It is most satisfactory that the London County Council, so soon after its constitution, should have cordially co-operated with the Vestries of Bethnal-green and Shoreditch in rooting out a nest of vice and disease, and replacing the miserable courts and alleys and insanitary and filthy houses with excellent buildings designed to provide comfortable houses for the working people. No doubt this change has not been effected without considerable expenditure. I learn that the cost of the land and properties which have had to be purchased was about £333,000, and that the cost of the buildings which have been erected amounts to nearly £300,000. But these provide accommodation for 5,380 persons, or only 339 less than the number who occupied the buildings which were demolished."

He followed this with an outline of advantages for the scheme stating that "The sum expended is undoubtedly large, but not large in proportion to the benefits which have been secured; for instead of some thousands of persons living under grave insanitary conditions, dying at the rate of which we have been told, breeding disease which is not only prejudicial to themselves, but which constitutes a danger to the whole of London, we have a population of almost the same size living under conditions which arc in every way favourable to health and comfort. There is, moreover, another view of the matter which may well be reckoned among the advantages which are gained. How little opportunity was there of social improvement among persons living under the conditions of those who previously inhabited this area! It may however, be asked, “Why do people continue to live under these unfavourable conditions?” I may quote the words of Dr. Southwood Smith: “They have no choice; they must live in what houses they can get, nearest the places where they had employment.” The conditions of the problem have changed of late years. The means of travelling from the centre to the outskirts of London are yearly growing easier, and we hope that this growth will be continuous."

In his third edition preface for 'A Child of the Jago' released in 1897, Arthur Morrison wrote about how ineffective he believed the Boundary Estate scheme to be:

"I have remarked in more than one place the expression of a foolish fancy that because the houses of the Old Jago have been pulled down, the Jago difficulty has been cleared out of the way. That is far from being the case. The Jago, as mere bricks and mortar, is gone. But the Jago in flesh and blood still lives, and is crowding into neighbourhoods already densely over-populated."

Genealogy

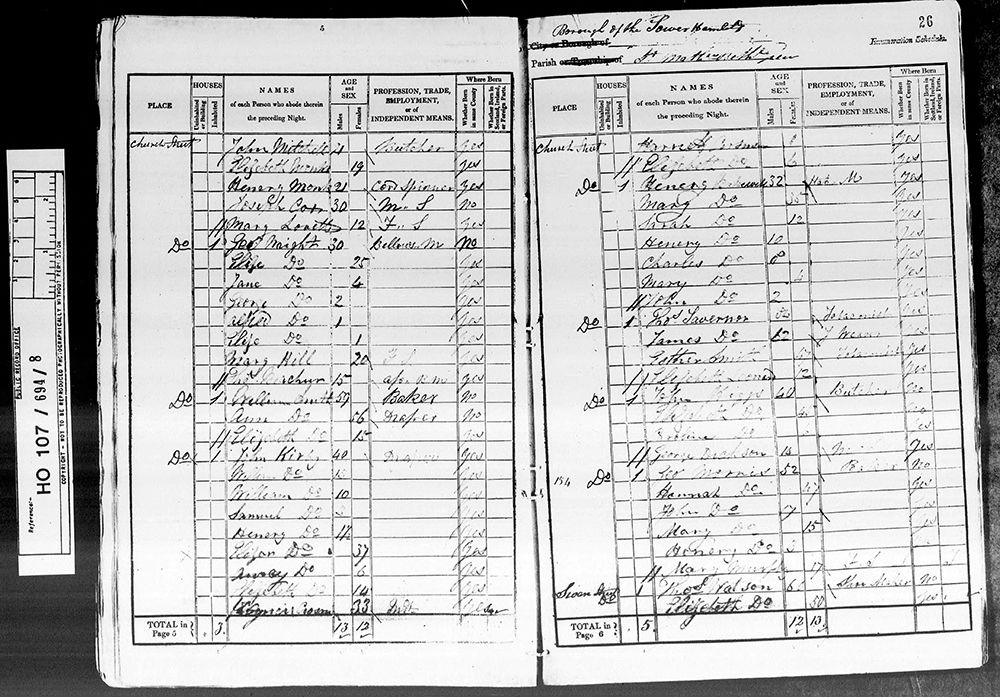

The 1841 census revealed that George William Wright, then 30 years old (born 1811) was a Bellows Manufacturer living with his wife Elizabeth and children Jane, George, Alfred, and Eliza. There is a Mary Hill present who at 20 years old may have been a domestic servant. Thomas Brachur is listed as a 15 year old assistant for bellows manufacturing.

By 1851 more children have arrived with the names James, Horatio, William, Octavius, and Edwin. Notable is the absence of Alfred. Also present is Charlotte Hemings a 20 year old domestic servant along with Ann Chick, a 46 year old nurse who was widowed. Unfortunately no census records could be found for 1861, but by 1871 at 110 Bethnal Green Road brothers James and Horatio Wright are both recorded as 'Journeyman Bellows Maker'. James had unfortunately been widowed at only 28 years old. Octavius was also present but recorded as a Smith. Elsewhere at 'The Shrubb' on Staines Road, Isleworth, Brentford is George William Wright listed as a Forge and Bellows Manufacturer at 60 years old. His wife Elizabeth is still with him along with his son William who at 25 years old has paralysis. His daughter Emily, grandson James H. Wright, and niece Mary Jane Shield are also present at the same address. Interestingly, a few doors down at 2 Cedar Cottages, Wellington Road is the Gask family including Clara who is listed as a governess caring for a 2 year old boy called George William Wright.

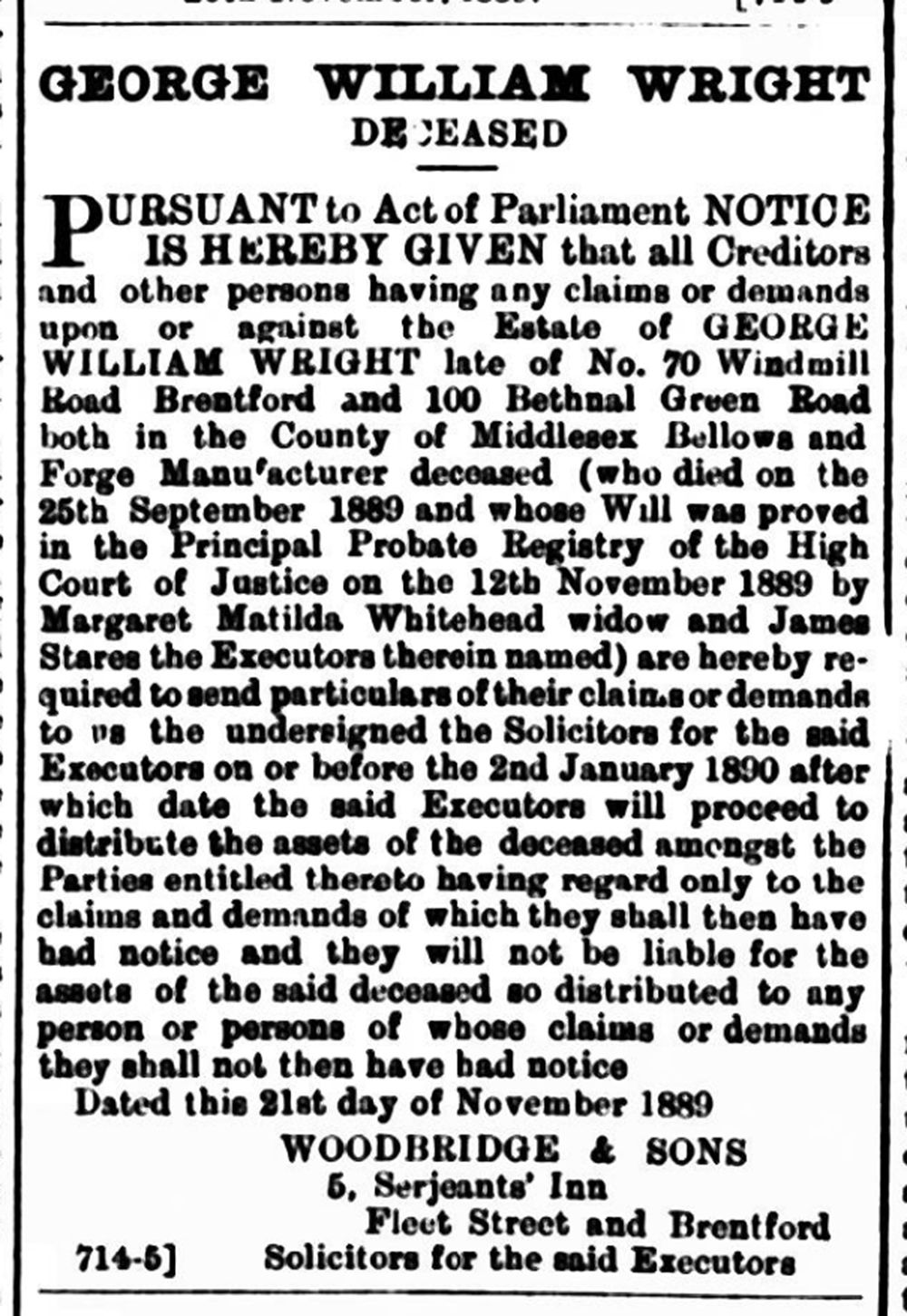

In 1881 four census records were found. James Wright, who has remarried to Elizabeth lives as a Bellows Manufacturer at 96 Leopold Buildings, a historical tenement built in 1872 on land leased by wealthy philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts. His son (likely from original marriage) is 16 years old working at a Mantle Warehouse. At 402 Hackney Road, Horatio is living with his wife Louisa and their children Albert, George, and William. Also present is Eliza A. Williamson and Esther Gross. At 190 Bethnal Green Road, William George Wright is a 25 years old Photographer living with his wife Sarah and their children William George and Albert George. 17 year old Elizabeth Harris is described as a 'General Servant'. George William Wright now 70 years old has moved to Blenheim Villas on Windmill Road in Brentford. It appears his wife Elizabeth has passed away by this point but 49 year old Margaret Matilda Whitehead is described as a servant. By 1891 George William Wright has died whilst Margaret is living at 70 Windmill Road on her own means with a 13 year old servant named Harriet Lucas. After searching in local newspaper records, an all revealing snippet was found which has been included below.

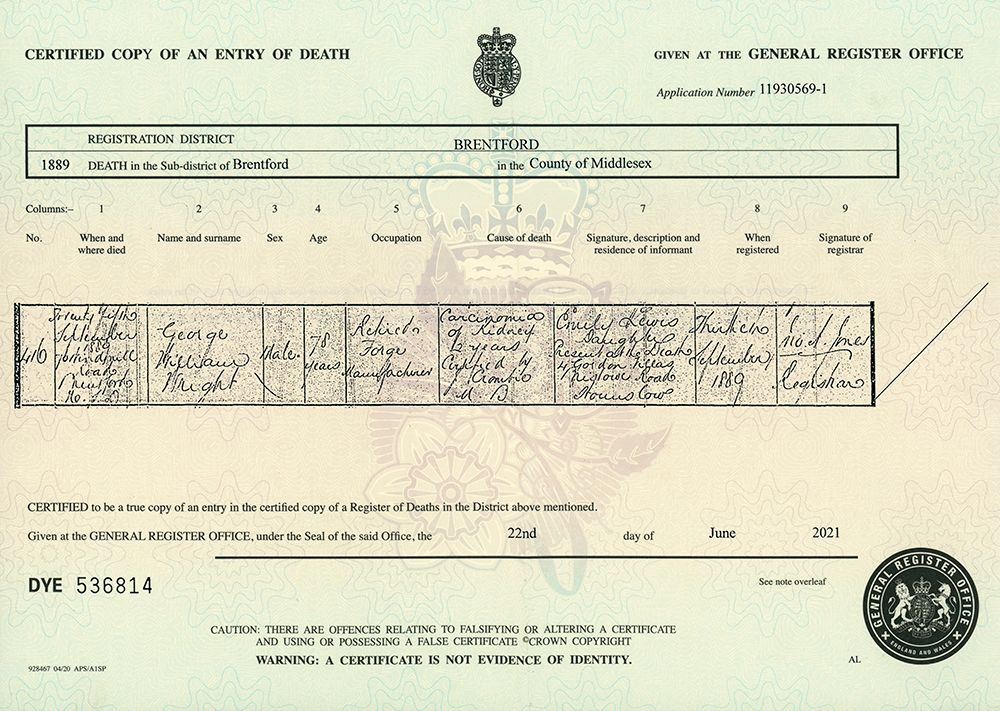

Margaret Matilda Whitehead is revealed to have been one of two executors of George William Wright's estate. We also find out that George had two permanent addresses, one of these is 100 Bethnal Green Road which is of course situated where many of his business interests were located. Below is George William Wright's death certificate which clearly states that he was a 'Retired Forge Manufacturer' who had carcinomatosis of the kidney. He battled with this for around two years before passing away at the age of 78 years old.

His will states a gross value of personal estate as £4045 11s. 9d. later resworn to £3895 11s. 9d. in August 1890. The Bank of England Inflation Calculator worked out that £3895 was £511,838.41 in 2020 with average inflation of 3.8 a year. Below is a full transcription of G. W. Wright's last Will and Testament:

This is the last Will and Testament of me George William Wright of No. 70 Windmill Road in Brentford, Middlesex. Bellows and Forge Manufacturer. I devise my two houses Percy Villas - Windmill Road aforesaid freehold to my housekeeper Margaret Matilda Whitehead for her life. And I bequeath to her the dividends to accrue on the sum of £1,900 2 3/4 per cent stock for her life. After her decease I devise and bequeath the said freehold houses and sum of stock to such of my children and in such shares and proportions as the said Margaret Matilda Whitehead by her Will shall appoint. And in deficit of appointment I devise and bequeath the same unto all my children then living in equal shares. I also bequeath to the said Margaret Matilda Whitehead the immediate legacy of £200 to be paid to her in priority to all other legacies bequeathed by this my will. I bequeath my business and book debts to my sons James, Horatio and Edwin in equal shares. And as to all the residue of my estate and effects I give divise and bequeath the same to my executors upon trust to sell and out of the proceeds in the first place to pay the following legacies: £500 to my daughter Elizabeth Stares, £300 to my son William, £200 to my daughter Jane Boorman, and £200 to my daughter Emily Lewis. And then to divide the remainder amongst all my children in equal shares. And I appoint the said Margaret Matilda Whitehead and James Stares my son in law Executors hereof. In witness where I have hereunto set my hand this 28th day of June 1889 - G. W. Wright - Signed and acknowledged by the said Geo. William Wright as his Will in the presence of us present at the same time & who in his presence and in the presence of each other have hereunto set our names as witnesses - Step. Woodbridge, Sol Brentford - Alfred Heath Clerk to Messrs Woodbridge & Sons Solicitors Brentford.

This is a Codicil to the within written Will dated twenty eighth June one thousand and eight hundred and eighty nine of me George William Wright of No. 70 Windmill Road in Brentford, Middlesex. Bellows and Forge Manufacturer. In addition to the devise and bequests contained in my said Will I bequeath to my housekeeper Margaret Matilda Whitehead the exclusive use and enjoyment for her life of my household furniture, books and plate linen china and other effects contained in my dwelling house and after her decease the same furniture and effects to go in the same manner as my freehold houses and sum of stock mentioned in my said Will And I bequeath to the said Margaret Matilda whitehead any ready money but not securities for money which may also be in my dwelling house at my death. In all other respects I confirm my said Will in witness whereof I have here unto set my hand this first day of July one thousand eight hundred and eighty nine. - G. W. Wright - Signed and acknowledged by the said George William Wright as a Codicil to his said Will in the presence of each other have hereunto set our names as witnesses. Alfred Heath and James Prince, Clerks to Messrs. Woodbridge & Sons Solicitors Brentford. On the 12th November 1889 Probate of this Will with a Codicil was granted to Margaret Matilda Whitehead and James Stares the Executors.

The Will clearly states Margaret Matilda Whitehead as executor but also top priority above all other relatives. This suggests that W. G. W. had a deep, meaningful relationship with his 'housekeeper' that meant he wanted her to live comfortably after his passing.

Moving forward an increment, it was revealed in the 1891 census that at 32 Old Ford Road in Bethnal Green, William George Wright is shown as a Licensed Victualler living with his wife Sarah and children William George, Albert Edward, Caroline Hannah, and Florence Lilian. There were also three bartenders present named Claud Bailey, John Alfred Jones, and Albert James Harrison. In addition to this there were also two general servants named Margaret Collins and Eliza Rose Commander. It is not clear why William George stopped practicing photography but it was found that he died less than ten years later according to the 1901 census. At this time his wife Sarah was living on her own means at 50 Francis Road, Low Leyton in West Ham along with their son Albert Edward Wright who at 23 years old had followed in his fathers footsteps as an art photographer. Also present is Albert's younger sibling Caroline Hannah along with Charlotte Commander who is perhaps a relative of Eliza Rose Commander who was recorded in the previous census.

To conclude, it is clear that the 'original' George William Wright was a particularly shrewd businessman above all else. With a clear attachment to Bethnal Green that spanned many decades, we can understand why he documented the poor children of London's East End with philanthropic intent. Through his background as a successful bellows and forge manufacturer, he would have already been capable of manufacturing photographic equipment which in turn made it worthwhile to pursue photography as a business. Photography was a volatile market in itself so it makes sense that there was revenue coming from other areas. The advantage of having numerous family members run branches of 'Wright's Photographic Studios' as they were opened in many different premises over the years would have continued to build on what was clearly a reputed family brand. It is not difficult to see how an empire could emerge from this carefully orchestrated operation. On this occasion it was not worked out how William George Wright was related to George William Wright as they seem to be neither one of his children or a child of his children. As G. W. W. was born in 1811 it is difficult to find out who his siblings were without ordering his birth certificate and finding out who his parents were.